A history of the St Andrew’s Ball in Montreal

|

By Gillian I Leitch

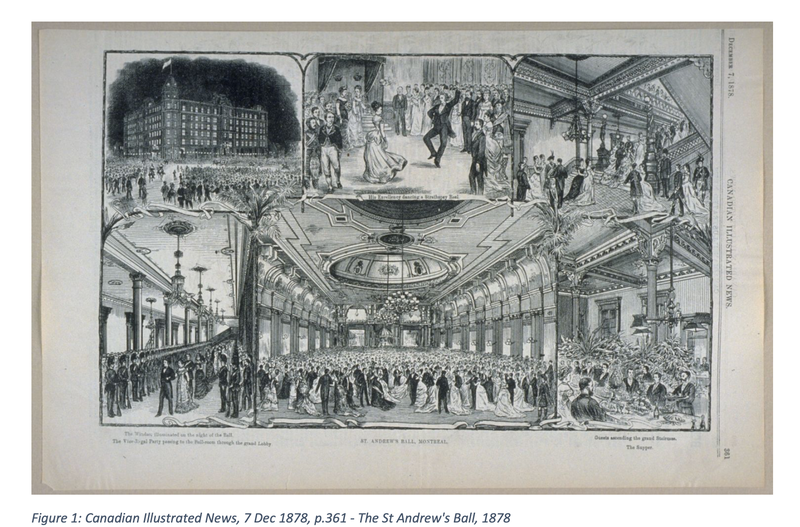

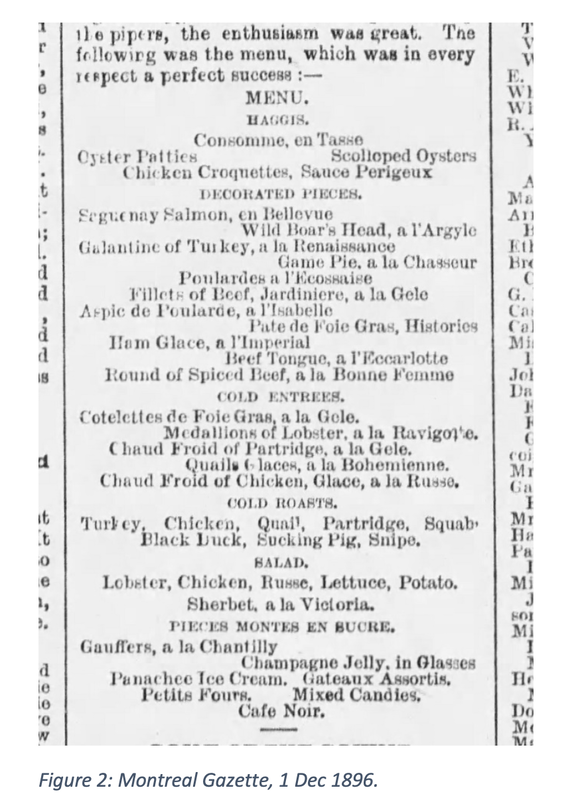

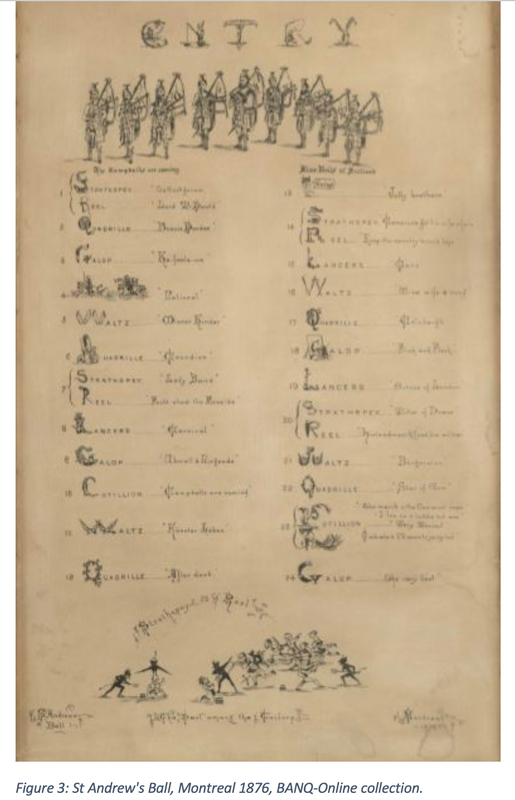

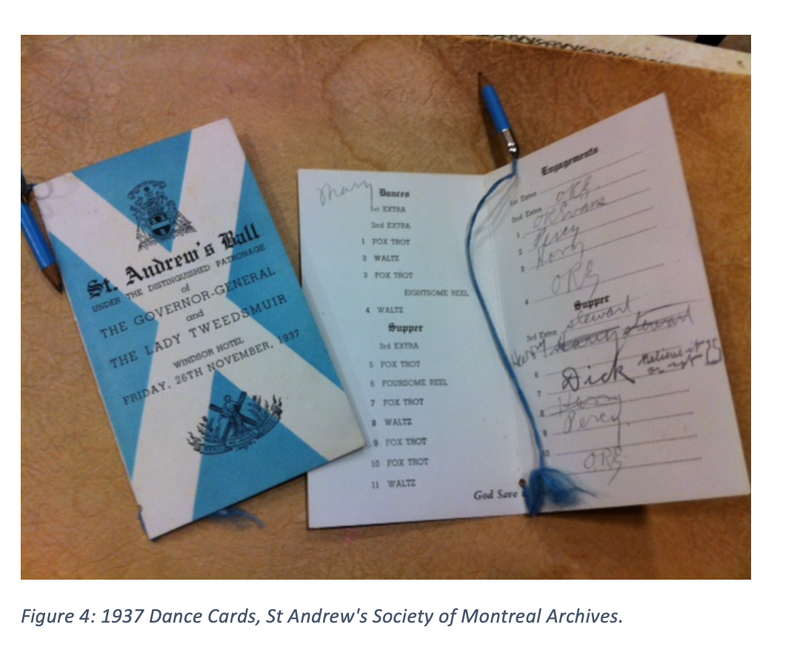

The St Andrew’s Ball has been a constant in Montreal’s season for well over a century. From its pipe bands, dances, debutantes, and tartans, the ball is full of ritual and tradition. The evening’s schedule is formal, yet familiar. This article will trace the ball from its earliest incarnation, and look at the various elements within the evening’s schedule, when they started, and the changes made over the years. Unfortunately, the archival record of the ball is incomplete. The Society does not have all the documents dealing with the organization of the ball, particularly its early years. More recent files deal to a large degree with the invitations to guests of honour, booking the venue and other administrative information. The ball’s elements are to a large degree not discussed because they are thought to be understood, known and traditional. To compensate for this silence in the archives, I have turned to the city’s newspapers for their descriptions of the ball, and the Society’s annual reports. The ball was until very recently regularly covered, in minute detail in the Montreal Gazette[1], from the decorations, the guests, the dances, and what everyone wore. The earlier the paper, the better the detail. Today’s St Andrew’s Ball The best way to talk about the evolution of the ball, and its traditions is to start with the ball as it is currently held. The ball starts in the early evening with a cocktail hour for the guests, and a President’s reception for the guest of honour in another room. There the guest of honour receives the dignitaries and committee members, in an intimate setting. The ballroom opens and the guests take their seats. The head table, with the guest of honour, is piped into the ballroom, where they take their seats. The national anthem is sung, and then grace is said. Before the main course is served, the haggis is piped into the ballroom, carried on a bier. The Robert Burns poem “To a Haggis” is performed, and the haggis stabbed with a knife. The guest of honour, the Society president, and Black Watch brass are then handed a quaich, and they toast the pipers. The pipers are then provided with their own portion of Scotch. The haggis and the dinner are then enjoyed. The guest of honour then gives a speech. The Queen is toasted, as is the Colonel in Chief of the Black Watch, and all the sister societies. Around 10 pm the guest of honour and other dignitaries are piped to the front of the ballroom, where they take a seat. The page(s) and flower girl(s) present the guest of honour and their spouse with a basket of flowers. The debutantes and their escorts are then presented to the guest of honour, the women curtseying, the men bowing. The debutantes and their escorts then perform a traditional reel, before the guest of honour and their spouse start the ball with a waltz. The dancing continues all evening, a mix of traditional Scottish country dancing and contemporary music. The ball ends around 2 am, when all the people still present gather on the dance floor and sing “Auld Lang Syne.” Ball Beginnings This set of events within the evening seem traditional, but would a ball guest from the past recognize them? The answer is probably a mix of yes and no. The St Andrew’s Society’s ball has evolved over the years. There have been a number of changes since its first ball in 1848, some subtle, some less so. The first ball held by the St Andrew’s Society was in 1848. Up to that year the Society had celebrated Scotland’s patron saint with all male dinners held in city hotels. The meals were characterized by their elaborate menus, plentiful toasts, and wine to go with both. The “Caledonian Assembly” in 1848 included the presence of Lord and Lady Elgin, and was hailed by the newspapers as a great success.[2] The next year they held a dinner. It was in 1871, about five years after women were able to become members of the St Andrew’s Society, that another ball was held. It was held at the St Lawrence Hall Hotel, in Old Montreal. It was a resounding success, and the Society held another ball at the same venue the next year. But as wonderful as the balls were, there was a group in the St Andrew’s Society which held onto the idea that the all-male dinner was the best way to celebrate the day. In the 1872 Annual Report it was noted that “the repugnance which was very naturally entertained by some of the more sedate members of the Society to this mode of celebrating the return of the national anniversary”[3] were overcome. But the balls were still not an annual event. In 1875 the Society held a concert instead of a ball. In 1878, the St Andrew’s Ball became “the” social event of the year, when the newly arrived Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne and his wife Princess Louise (daughter of Queen Victoria) were the guests of honour. The ball, which was held at the Windsor Hotel, started at 9 pm, when the guests of honour were piped into the ballroom, accompanied by the 5th Fusiliers. The Governor General made a speech, and then the guests of honour danced the Vice-Regal set dance. The dancing continued to around midnight when the guests retired to another room for a supper. After eating their fill from a very large and elegant selection of foods, the guests returned to the ballroom to continue dancing. The guests of honour left at 1 am, but the rest of the company stayed dancing until 4 am.[4] This ball was “THE” event of the year, and all subsequent balls were compared with it. A few weeks before the 1883 celebrations, the Montreal Herald reviewing the 1878 ball in detail. In 1881, the description of the ball was quick to point out “the scene was a most brilliant and animated one, even rivalling that of the well-remembered occasion in 1878 when Her Royal Highness the Princess Louise honoured the St Andrew’s Society by appearing at their annual ball.”[5] Despite the apparent popularity of the ball, and of the 1878 one in particular, there were years when the day was celebrated in another fashion. In 1879 they held a banquet, and again in 1895. It is clear that the main issue of the issue of how to celebrate the day was linked to the role women were thought to play in the Society, and perhaps in the members’ idea of what it meant to be Scottish. In the 1884 Annual Report it was put in this way: There is no question that a ball is the more generally popular mode of celebrating the day so dear to Scottish hearts, in that it enables the fair sex to take part, to contribute so much to the pleasures of the occasion, and to share in its joyous nature.”[6] For a Society which was still run by men (women members were not on Council and were only a part of the Charitable Committee) this was a change that was hard to make. It was only from 1896 on that the Society chose to use the ball as its principle celebration of St Andrew’s Day.[7] Great Chieftain of the Pudding Race The first mention of the haggis was in 1886, when the Haggis was served at the supper. It was carried into the supper room by “four stalwart Highlanders, in costume.”[8] The newspaper accounts afterwards focus on how the haggis was borne into the supper room, the sturdiness of the men carrying it, and their highland costumes. In 1901 the haggis was set ablaze during its journey through the supper room, and was placed next to two suckling pigs wearing a kilt with glasses in their paws.[9] There is actually no mention of the Robert Burns poem “To a Haggis” being recited in any of the accounts throughout the next 100 years. Some years, by the descriptions provided the haggis ceremony as it was described was only the procession of the haggis into the room, with pipers, and the haggis being cut. In 1983, “Following the ceremonial entrance of the Haggis, its skin was pierced with one decisive slash of Sir William’s [Macpherson of Cluny] dirk. In a ringing voice he declared, “I sentence this haggis to DIE.”[10] There are two possibilities to explain the silence on the poem being recited. The first is that it was not recited, and the haggis itself was considered the event, along with the way in which it was brought into the room before being consumed. The second is that the poem was always recited, but was not considered important to state – the visual of the haggis itself was enough to note. Food, Glorious Food Food has always played a part in the evening’s celebrations. In the early years, the ball started in the evening around 9 or 10 pm, and a supper was served around midnight. The meal provided was elaborate, sometimes served buffet style, but mostly as a sit-down meal. The menu in figure 2, from 1896 is an example of the elaborateness of the menu at the balls. While supper is usually defined in dictionaries as usually a light meal served before bed, the sheer quantity of food on offer, belies this. It should be noted that in the newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s, it was usual that those who were attending the St Andrew’s Ball, would announce in the newspapers – in the Society section, that they were dining with their own group at a local hotel, often the Ritz, before going to the ball. Such as Mrs. Clarence Dumaresq, who was “entertaining at dinner this evening in honor of her guests, Mr. and Mrs. Charles McGill of Toronto, and will take her guests on to the St. Andrew’s Ball.”[11] The guests of honour also would dine privately before the ball with the President of the Society and other dignitaries. In 1967, the supper at the ball was dropped in favour of a dinner, which was served prior to the ball. That year a “Highland Dinner” was held in a separate room, prior to the ball. Dinner replaced supper. By this time the menus were not nearly as elaborate as they had been earlier in the century. The haggis ceremony was moved from midnight to some time during the dinner. An informal breakfast was added to the schedule, starting at 1:30 am.[12] This was not the first time a breakfast was offered. In 1961 there was a breakfast available on request, and for an additional fee at 4:45 am.[13] But this informal breakfast was less elaborate, and served much like the suppers used to, as a break for those dancing in the middle of the evening. The shift to an earlier start also created an opportunity for pre-ball socializing. A President’s reception was added for the guest of honour to meet the invited guests, committee members, and other dignitaries, while the rest of the ball guests would attend a cocktail hour prior to the beginning of the dinner. The dinners started around 7-8 pm. Coming Out One of the most unusual things about the St Andrew’s Ball is the presence of debutantes. It is now only one of two balls held in Montreal which provides the opportunity of debutantes, the other is the Viennese Ball. Debutantes have been an important part of the St Andrew’s Ball since the 1890s. Their presence added youth and beauty to the affair, and the newspapers were full of glowing descriptions of the ladies, their charm and their dresses. A debutante is a young woman who is considered old enough to be presented to society. The ultimate goal was for the young lady to meet a socially acceptable young man, and marry. The coming out, or debut was done at a ball held by either their families, or a public ball, like the St Andrew’s Society of Montreal. While a select few people such as Sir Hugh Allan included a ballroom inside their fancy homes, most Montrealers did not have that facility. Balls were though, important and frequent events in Montreal’s “social calendar” so a lot of balls, even private ones, were held in the city’s hotels. There were throughout the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century a whole season of events which provided the opportunity to be presented, and the choice made by the parents as to where their daughter will come out, was important. The St Andrew’s Ball had the advantage of Vice-Regal presentation, which meant that the monarch’s representative normally the Governor General, but also other members of the British Court, were present – although not every year.[14] In a pinch, there was always the Lt-Governor of the province.[15] In the early 20th Century debutantes could also be presented in Ottawa, at the opening of Parliament.[16] A Vice-Regal presentation then was considered an honour, and much better than just a debut. It was prestigious, not as good as being presented in London, directly to the Queen, but a social distinction many wanted. When the Queen ended Court presentations in London in 1958, the Governor General continued to attend debutante balls elsewhere.[17] The decline of other debutante opportunities after 1958, meant that the St Andrew’s Ball had an added alure of being one of the few places presentations occurred. A debutante is usually visible in a crowd because she is wearing white. In 1901 the scene at the ball was described this way: “The gowns worn were particularly handsome, the white dresses of the debutantes present forming a pleasing contrast to the darker gowns donned by many of the chaperones, and the bright-hued garments of the girls who have been out for a year or two.”[18] There were no hard and fast rule however that they had to wear white. Throughout the early 20th century debutantes’ dresses were described in detail, and many wore other colours, such as Miss Isobel Paterson in 1913, who wore a “pink charmeuse gown with lampshade tunic of chiffon, edged with ermine and an old pink cameo ornament.”[19] Or, Miss Ailsie Coghlin in 1923 who wore a “pink georgette draped in platinum lace and showered with rainbow ribbon.” Miss Beatrice Murray wore “a gown of blue crepe romaine over orchid, with touches of pearl trimming, embroidered in blue and crystal beads in floral effect,” that same year.[20] It does not appear to have been enforced until 1939, when the descriptions of the debutantes all mention that they are wearing white.[21] The tartan sash did not make its appearance in the costume of the debutante until 1946. That year the Hon Diana Rodney was pictured wearing a tartan sash.[22] By 1954 debutantes who were of Scottish descent were described wearing their family tartans in the descriptions of their dresses.[23] The rules for the debutantes became stricter, and as discussed in an article in 1960, they were obliged to wear white floor-length dresses, white gloves, and a sash in their clan tartan if they had Scottish ancestry.[24] Now all debutantes wear a tartan sash. Those without Scottish roots, are lent one in the “Montreal 1642” tartan.[25] From the beginnings of the St Andrew’s Ball, debutantes were not all of Scottish descent. Looking at the list of debutantes over the years, it is evident that women from all of the ethnic and linguistic groups have been presented at the ball.[26] For example, Lorraine Cuddy, who was presented in 1929, was Irish,[27] Dorothy Molson, who was presented in 1923 was English. There were also a number of women from other cities in Canada and the United States, notably Ottawa. To be a debutante it was just a matter of knowing a member of the Society and having her name proposed to the ball committee. Some years the Society actually advertised for ladies to propose themselves as debutantes.[28] All debutantes though had to go through a vetting process.[29] With such a large pool of women to draw from, it meant there were some years when there were a lot of debutantes. Between 1897 and 1936 there were usually around 20-30 debutantes each year, with only a few special years when there were more, such as 64 in 1924 and 75 in 1929. Just before the Second World War and 1967, the numbers ranged from the low in 1938 of 36 and the high in 1945 of 171. 1967 was the last year when there were more than 20 debutantes presented at the ball, 35. Since that time the numbers have declined, and the ball normally attracts between 6 and 10 debutantes a year. Dancing the Night Away The most important aspect of a ball is of course the dancing. And it is here that there have been the fewest changes in the way things run at the St Andrew’s Ball. The dancing still starts around 9:30 -10 pm, and goes to the early hours of the next morning. The dances also haven’t changed much, in that there is still a mix of traditional and contemporary dancing. The earliest list of dances was in 1876.[30] The end of the ball in this case was with a “Galop,” but in the latter part of the 19th century, the ball tended to end with the “Sir Roger de Coverly.” In 1900, the ball was ended with “Auld Lang Syne” danced either as a waltz, or sung by the guests, as it continues to do. From the earliest balls there were mentions of dance cards, how beautiful they were, the quality of the paper, the elegance of script and of course the colour of ribbon which held it together. The dance card is the way in which people could plan their evening. The filling out of the card took up the first block of a person’s time upon arrival at the ball. For example, in 1901: “The guests began to arrive a little after nine o’clock, but it must have been fully ten when, the preliminary greetings over and the dance cards filled, everyone adjourned from the hotel drawing rooms and corridors”[31] In 1896 the organizing committee decided to split the ballroom up into shires, named after the Shires in Scotland. Each person was assigned a shire where they could stand when not dancing, and the dance card had an extra spot where the person could write out where they were assigned so their partner could find them when the time came to dance together.[32] It is not clear when the Society ceased using dance cards. The Archives have examples from 1937 and 1939, but not before, and none since. The newspapers do not talk about dance cards after the 1920s. The Society continued though to publish sheets with the list of the dances set out for the evening. By the 1960s, only the dances which were considered traditional, i.e., the Scottish Country Dancing, were listed. From the 1920s onwards the Society also arranged for dance practices for those interested in learning the traditional dances. Something the Society continues to do. Conclusion The survival of the St Andrew’s Ball to the present has been in large part because of the changes that have been made over the years. The use of ceremony such as with the presentation of the haggis (although the ceremony itself might have changed) and the presentation of the debutantes to the guest of honour (and the Society) links the members to their Scottish past. The ball retains a number of elements from the nineteenth century such as the dancing, the music, the haggis, and the tartans, but has evolved so that these traditional elements continue to have meaning to its members. [1] This is an article that was written in Covid 19 Isolation, so I used only online sources and material that I had already gathered in my home. The Montreal Daily Star was also very good at covering the St Andrew’s Ball, but it is only available in libraries on microfilm. [2] Montreal Gazette, 4 Dec 1848; Pilot, 5 Dec 1848. [3] Thirty-Seventh Annual Report of the St Andrew’s Society of Montreal from November 4th, 1871 to November 1872, Montreal, John C Becket, 1872, p. 19. St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Archives. [4] Ottawa Citizen, 2 Dec 1878. [5] Montreal Herald, 1 Dec 1881, p. 8. [6] Forty- [7] The Society also held an annual religious celebration of St Andrew’s Day in one of the city’s Presbyterian Churches, and until the 1880s also had a parade which brought the members to the church before the service. The Annual General Meeting was also held near or on St Andrew’s Day until the 20th century, when it was moved to reflect the fiscal year. [8] Fifty-First Annual Report of the St Andrew’s Society of Montreal, November 30th 1885 to November 30th 1886, Montreal, St Andrew’s Society, 1887, p. 23-24. St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Archives. [9] Montreal Gazette, 30 Nov 1901. [10] Montreal Gazette, 28 Nov 1983. [11] Montreal Gazette, 30 Nov 1921. [12] Montreal Gazette, 2 Dec 1967. [13] Montreal Gazette, 7 Nov 1961. [14] A list of the guests of honour can be found here: https://www.standrews.qc.ca/st-andrewrsquos-ball-guests-of-honour.html [15] The Governor General required a full curtsy, while the Lieutenant Governor required only a half-curtsy. [16] Elise Chenier, “Class, Gender and the Social Standard: the Montreal Junior League, 1912-1939,” Canadian Historical Review, Vol 90, no 4, (Dec 2009), p. 679. [17] Saskatoon Star Phoenix, 25 Jan 1958. [18] The St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Sixty-Seventh Annual Report 1901-1902, Montreal, St Andrew’s Society, 1903. St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Archives. [19] Montreal Gazette, 6 Dec 1913. [20] Montreal Gazette, 1 Dec 1923. [21] Montreal Gazette, 1 Dec 1939. [22] Montreal Gazette, 30 Nov 1946. [23] Montreal Gazette, 27 Nov 1954. [24] Montreal Gazette, 29 Oct 1960. [25] https://www.standrewsball.com/debutantes-and-escorts.html (accessed 17 May 2020) [26] See list of debutantes here: https://www.standrews.qc.ca/st-andrews-ball---debutants-flower-girls-and-pages.html [27] Daughter of Sarsfield Cuddy and Estelle McKenna. [28] Montreal Gazette, 22 Nov 1940. [29] Montreal Gazette, 29 Oct 1960. [30] St Andrew’s Ball, Montreal 1876, BANQ Online - http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/3197365 (accessed 17 May 2020) [31] The St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Sixty-Sixth Annual Report 1900-1901, Montreal, St Andrew’s Society of Montreal, 1902 p. 32. St Andrew’s Society of Montreal Archives. [32] Montreal Gazette, 1 Dec 1896. [33] Forty-First Annual Report of the St Andrew’s Society of Montreal from November 1st 1875 to November 1st 1876, Montreal, John C Becket, 1875, p. 28. [34] For more about the epidemic see here: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/plague-the-red-death-strikes-montreal-feature [35] For more about Sir Henry Lauder see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Lauder [36] For more about Dame Gladys Cooper see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gladys_Cooper [37] The list of debutantes can be accessed here: https://www.standrews.qc.ca/st-andrews-ball---debutants-flower-girls-and-pages.html |

Fun Facts:

|